IN Zimbabwe, elections are more than just a political process; they are a litmus test for the nation’s democratic aspirations and a reflection of its tumultuous history.

Since gaining independence from British colonial rule in 1980, Zimbabwe has held regular elections, but the promise of democracy has often been overshadowed by allegations of fraud, violence, and authoritarianism.

As the country prepares for its next electoral contest, the stakes could not be higher.

The ballot box remains both a symbol of hope and a source of peril, encapsulating the enduring struggle for freedom, fairness and accountability in one of Africa’s most politically-charged nations.

Zimbabwe’s electoral history is deeply intertwined with its political evolution.

The first post-independence election in 1980, which brought Robert Mugabe to power, was widely seen as a triumph of liberation and self-determination.

However, over the next four decades, Mugabe’s rule became synonymous with repression, economic decline and electoral manipulation.

Elections under his leadership were often marred by violence, intimidation and allegations of rigging, turning what should have been a democratic process into a tool for consolidating authoritarian control.

- Is military's involvement in politics compatible with democracy?

- Feature: Is Auxillia following in 'Gucci' Grace's path?

- Mnangagwa govt harasses opposition with arrests, jail

- Sadc meets over water, energy and food security

Keep Reading

The crisis was only resolved through a power-sharing agreement brokered by the Southern African Development Community (Sadc), but the scars of 2008 remain etched in the national memory.

The post-Mugabe era: A new dawn?

When Mugabe was ousted in a military coup in November 2017, many Zimbabweans hoped it would mark the beginning of a new era.

His successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, promised to usher in a “new Zimbabwe” characterised by democracy, economic reform and reconciliation.

The 2018 election, the first without Mugabe on the ballot, was viewed as a critical test of these promises.

Initially, the election was met with cautious optimism.

International observers, including those from the African Union and Sadc, noted improvements in the pre-election environment, such as greater political space and a more inclusive voter registration process.

However, the optimism was short-lived.

On election day, reports of voter suppression, ballot box tampering and delays in releasing results raised serious concerns about the credibility of the process.

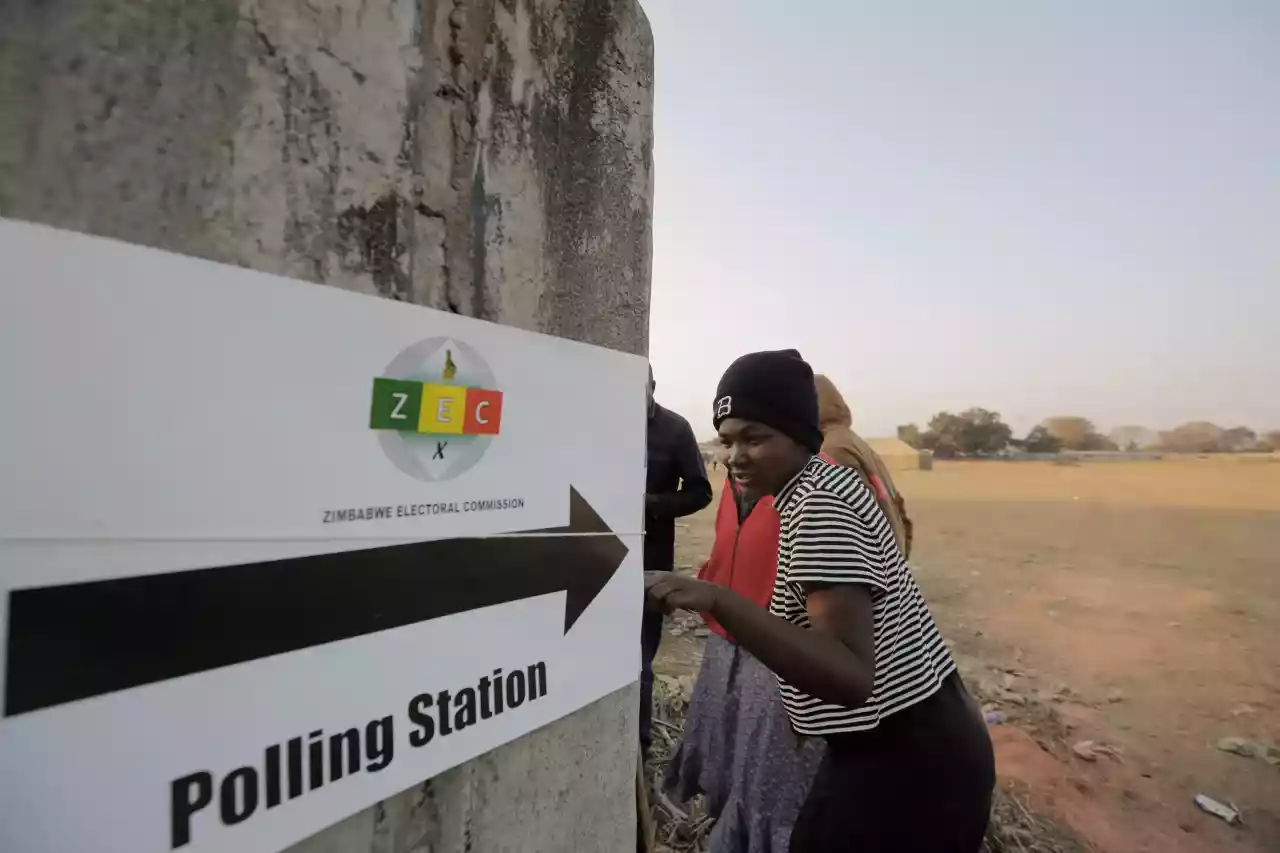

When the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec) announced Mnangagwa as the winner, the opposition MDC-Alliance rejected the results, alleging widespread fraud.

The youth demographic: A sleeping giant

Zimbabwe’s youth bulge is both a blessing and a challenge.

With a median age of just 20 years, the country has one of the youngest populations in the world.

This demographic dividend holds immense potential for economic growth, innovation and social transformation.

However, it also presents a pressing challenge: How to engage a generation that feels increasingly disillusioned with the political process.

Cultural and institutional barriers further compound the problem.

Zimbabwe’s political landscape is dominated by older generations, with little room for young leaders to emerge.

The ruling Zanu PF party and the main opposition, the Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC), are both led by figures in their 50s and 70s, creating a perception that politics is a space for the elderly.

This generational gap is reinforced by traditional norms that equate age with wisdom and experience, often sidelining the voices of young people.

Despite these challenges, there are signs of a growing youth movement demanding change.

In recent years, young Zimbabweans have become increasingly vocal in their calls for political and economic reform.

Social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook and WhatsApp have become powerful tools for mobilisation, enabling youth to bypass traditional gatekeepers and amplify their voices.

The 2016 #ThisFlag movement was a watershed moment for youth activism in Zimbabwe.

What began as a social media campaign quickly evolved into a nationwide protest against corruption, economic mismanagement and political repression.

Although the movement was eventually suppressed, it demonstrated the potential of youth-led initiatives to challenge the status quo.

Similarly, the 2020 #EndSARS protests in Nigeria inspired Zimbabwean youth to take to the streets under the banner of #ZimbabweanLivesMatter.

The protests, which were largely organised and driven by young people, highlighted issues such as police brutality, unemployment and governance failures.

While the government responded with a heavy-handed crackdown, the protests underscored the growing restlessness of Zimbabwe’s youth and their willingness to fight for change.

The road ahead: Rebuilding trust in democracy

As 2025 unfolds, Zimbabwe’s electoral calendar is packed with tests, as the nation prepares for its next election, the challenge is to rebuild trust in the democratic process.

This will require comprehensive electoral reforms, including the establishment of an independent and transparent Zec, the depoliticisation of State institutions and the creation of a level playing field for all political parties.

Strengthening the rule of law, ensuring the independence of the Judiciary and protecting freedom of expression are also critical steps towards creating an environment conducive to free and fair elections.

Civil society and the media must continue to play their part in holding leaders accountable and advocating for change.

At the same time, regional and international actors must adopt a more co-ordinated and principled approach, balancing pressure for reform with support for dialogue and reconciliation.

Ultimately, the future of democracy in Zimbabwe lies in the hands of its citizens.

Despite the challenges, Zimbabweans have shown remarkable resilience and determination in their pursuit of freedom and justice.

The ballot box remains a powerful tool for change, but its potential can only be realised if the process is free, fair and inclusive.

Lastly, as Zimbabweans go to the polls, they do so not just to choose their leaders, but to affirm their belief in the possibility of a better tomorrow.

The question is whether the nation’s political elite will rise to the occasion and honour the will of the people or the peril of electoral politics will once again overshadow the promise of democracy.

The answer will shape the destiny of Zimbabwe for years to come.

- Tariro Sande and Ruvarashe Makanza are students at Africa University in the department of International Relations & Diplomacy