INFORMALISATION — the shift of economic activities from the formal, regulated and tax-paying sector to the unregulated and untaxed informal sector — has become a defining feature of Zimbabwe’s economy.

By 2024, the informal sector accounted for approximately 60% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and employed over 76% of its workforce, according to the African Development Bank.

While this sector provides critical livelihoods for millions, its dominance signals deeper structural challenges.

Over the past five years, Zimbabwe has witnessed the exit of multinational corporations and the closure of many local firms, further weakening the formal economy.

This article examines the causes of informalisation, its impacts, global examples of solutions and policy options available to address this phenomenon.

Composition of informal economy

Zimbabwe’s informal sector is diverse, with its largest contributors being street vending (40%), artisanal mining (30%), and informal transport (20%).

Smaller contributors, categorised as “other informal activities”, account for the remaining 10%. This composition reflects the resourcefulness of Zimbabweans in adapting to economic challenges but also underscores systemic issues in the formal economy, such as inadequate job creation and limited industrial capacity.

- Zim headed for a political dead heat in 2023

- Record breaker Mpofu revisits difficult upbringing

- Tendo Electronics eyes Africa after TelOne deal

- Record breaker Mpofu revisits difficult upbringing

Keep Reading

Causes of informalisation

Zimbabwe’s informalisation stems from persistent economic instability, high unemployment, and structural and policy-driven factors that have pushed businesses and individuals toward unregulated activities.

Macro-economic instability

The country’s volatile macroeconomic environment, marked by hyperinflation, currency volatility, and repeated changes in monetary regimes, has eroded confidence in the formal sector.

For example, the introduction of the gold-backed Zimbabwe gold (ZiG) currency in April 2024 was intended to stabilise the economy. However, a 43% devaluation by September undermined its credibility, driving businesses and individuals to seek refuge in the informal sector.

Companies struggling to cope with these dynamics, such as Unilever, exited Zimbabwe in 2024 after 80 years of operations, citing an unfavourable business environment.

Similarly, Standard Chartered Bank and Deloitte departed in recent years, reflecting the difficulties faced by formal enterprises.

High unemployment rates

Zimbabwe’s formal unemployment rate exceeds 90%, leaving millions without stable job opportunities. The collapse of industries, such as manufacturing and commercial agriculture has forced people into informal activities like street vending, artisanal mining, and informal transport services.

Corporate closures, such as Standard Chartered Bank’s exit in 2022 after 130 years, have worsened this trend, with the informal economy serving as a critical lifeline.

Regulatory and compliance barriers

Excessive regulation and high compliance costs also contribute to informalisation. Zimbabwe ranks 140th out of 190 countries on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index for 2024.

Businesses face high taxes, complex licencing requirements, and unpredictable policy changes, which deter formal registration.

In industrial hubs such as Bulawayo, over 60% of companies had ceased operations by 2021, opting to transition to informal operations or shut down entirely.

Structural and historical factors

The legacy of Zimbabwe’s land reform programmes and economic crises, particularly during the hyperinflationary period of 2008–2009, has left the economy vulnerable.

Many formal enterprises have downsized, transitioned to informal models, or closed outright. Between 2017 and 2018, 55 companies were liquidated, further fuelling informalisation.

Global pressures, such as declining commodity prices, and climate challenges, like the 2024 El Niño-induced drought, have compounded these issues.

This drought, the worst in 40 years, devastated agricultural output, leaving 40% of Zimbabweans food insecure and forcing rural households to turn to informal income-generating activities.

Effects on formal corporate sector

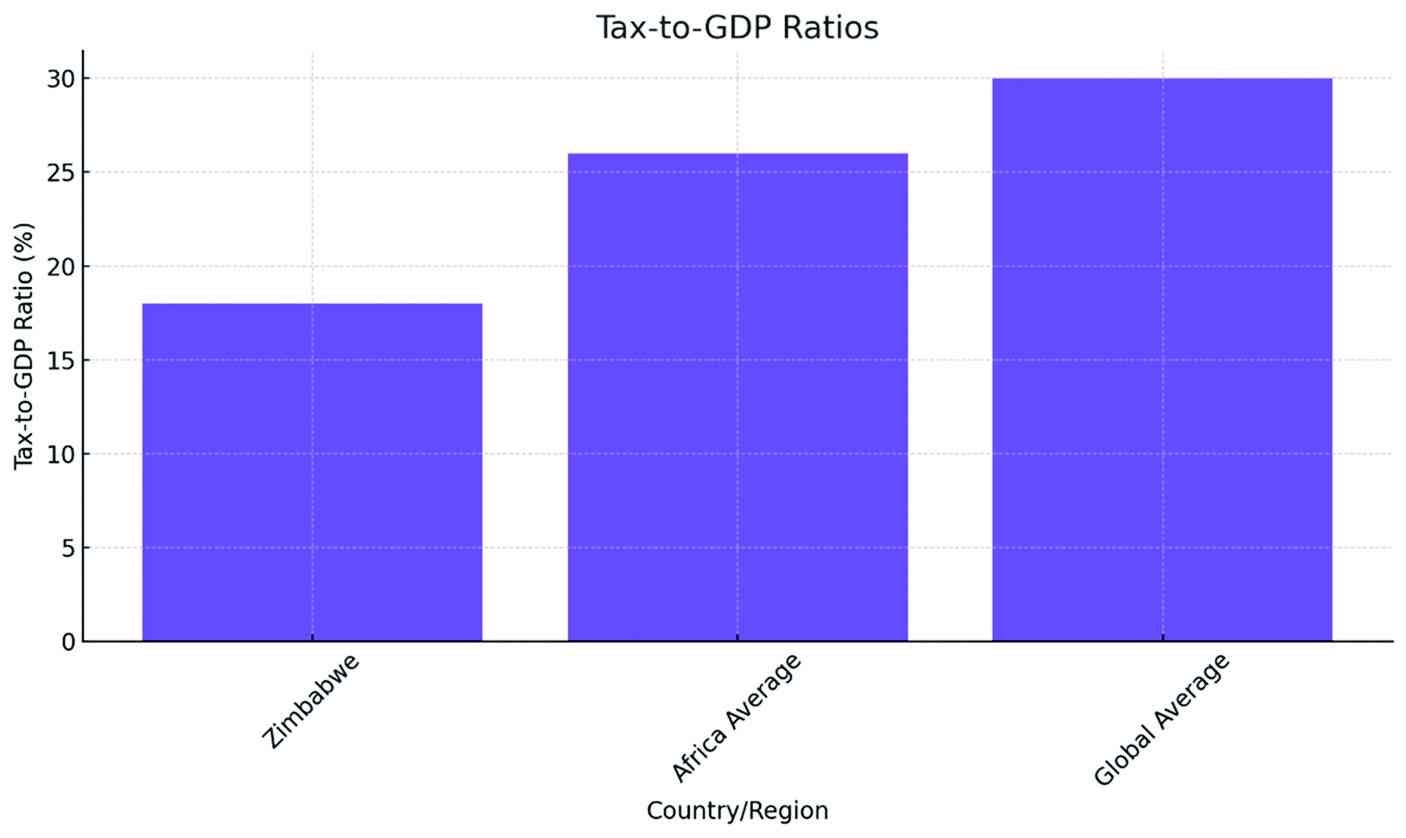

The dominance of the informal economy undermines the formal sector by reducing government revenue and eroding investor confidence. Zimbabwe’s tax-to-GDP ratio, at below 20%, is significantly lower than the African average of 26% and the global average of 30% (Source: IMF and Ministry of Finance).

Informal businesses, which bypass taxes and labour regulations, compete unfairly with formal enterprises, destabilising industries. This dynamic has driven companies like Deloitte to exit Zimbabwe, as reduced activity among multinationals made formal operations unsustainable.

Broader economic impacts

While the informal sector provides livelihoods for millions, its predominance limits Zimbabwe’s long-term economic growth. Informal businesses lack access to credit, technology, and economies of scale, reducing productivity and innovation.

Weak tax revenues constrain public investments in infrastructure, healthcare, and education, while workers in the informal sector remain vulnerable without pensions, health insurance, or labour protections.

For instance, the closure of 31 microfinance institutions in 2021 highlights broader challenges in accessing capital for both formal and informal actors.

Lessons from other countries

Zimbabwe can draw inspiration from countries that have addressed informalisation effectively:

India’s digital and tax reforms: India’s informal sector accounts for nearly 80% of employment, similar to Zimbabwe. To address this, India introduced digital payment systems and simplified tax structures under the Goods and Services Tax regime, encouraging informal enterprises to join the formal economy. Microfinance initiatives have further supported small-scale entrepreneurs, enabling them to access credit and scale their businesses.

SA’s support for small businesses: South Africa has implemented policies that support small businesses, including subsidies, training programmes, and improved market access. Establishing township hubs has helped informal traders become more productive and organised.

Colombia’s simplified registration: Colombia’s efforts to formalise its economy included simplified business registration processes and tax incentives. These measures significantly increased the number of businesses transitioning to the formal sector.

Kenya’s market integration: Kenya has invested in infrastructure development, cooperatives, and tailored financing solutions to integrate informal traders into the mainstream economy. These strategies have improved productivity and compliance while preserving the dynamism of the informal sector.

Policy solutions for Zim

To manage informalisation, Zimbabwe must adopt a multi-faceted strategy that stabilises the economy, encourages formalisation, and protects vulnerable workers.

Macro-economic stability

Transparent monetary policies and sufficient foreign exchange reserves can restore confidence in the local currency and reduce reliance on informal mechanisms. Simplifying regulatory frameworks would further incentivise formalisation. For example, a one-stop-shop model for business registration, as seen in Colombia, could reduce bureaucratic hurdles and compliance costs.

Access to credit and insurance

Expanding access to affordable credit and insurance for small enterprises is critical. Microfinance institutions can play a pivotal role in helping informal businesses transition to formal operations.

Extending social safety nets, such as health insurance and pensions, would provide security and encourage formalisation. Conditional benefits tied to compliance with registration requirements could also be effective.

Investments in infrastructure

Designated trading spaces with utilities and sanitation would improve conditions for informal traders while fostering regulation and oversight. Public awareness campaigns can educate businesses and workers about the benefits of formalisation, such as access to financing, protections, and growth opportunities.

International partnerships

Collaboration with international partners like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund can provide funding and technical expertise to support reforms. Such partnerships can also help Zimbabwe attract investment and improve its business environment.

Conclusion

Informalisation in Zimbabwe is a symptom of deeper structural challenges, including macroeconomic instability, high unemployment, and inadequate policy frameworks. While the informal sector provides critical livelihoods, its dominance threatens long-term economic growth and fiscal stability.

Lessons from countries like India, South Africa, and Kenya demonstrate that targeted interventions — ranging from regulatory simplification to financial inclusion — can effectively address informalisation.

By prioritising these reforms, Zimbabwe can transform its informal economy into a foundation for sustainable growth and resilience, aligning with its Vision 2030 goal of achieving upper middle-income status.

Addressing informalisation is not just an economic necessity — it is essential for creating a future of opportunity and stability for all Zimbabweans.

- Chikosi, a former director at the World Bank, now serves as an independent director on the boards of prominent local and international companies. With a wealth of experience in global development and corporate governance, he is dedicated to fostering growth, driving sustainable solutions and offering strategic insights into Zimbabwe’s economic challenges and opportunities.