ZIMBABWE’s treasury department presented a ZW$4,5 trillion budget (21% of 2021 GDP) for the 2023 fiscal year. The budget roughly translates to US$5,3 billion if the market exchange rate is used.

As is the case over the past 10 years, revenue collections will fall way below expenditure resulting in an anticipated budget deficit of at least ZW$0,6 trillion which will be funded through issuance of treasury bills (TBs), issuance of US dollar denominated bonds and external loan disbursements. The budget estimated that Zimbabwe’s nominal GDP for 2023 will hit ZW$21.8 trillion (Approximately US$25,65 billion).

The economy is expected to grow by 3,8%. To achieve the above growth, treasury assumes that there will be favourable international commodity prices, tight monetary and continued use of the multi-currency.

According to the government, key risks for 2023 emanate from the uneven distribution of rainfall, power cuts and contingent liabilities from State Enterprises and Parastatals (SEPs). However, there are glaring priorities that need to be addressed in 2023 in order to address the recurring economic instability in the country.

These include:

Currency stability and inflation

Despite the drop in month-on-month inflation from 3,2% recorded in October to 1,8% realised in November 2022, consumer prices keep rising every month.

With annual inflation likely to end 2022 at over 260%, there is no doubt that currency instability lies at the heart of Zimbabwe’s economic instability and the price distortions that are rife in the local market.

- Experts downbeat as Ncube cuts GDP forecasts

- New perspectives: De-link politics from Zim’s education policies

- Experts downbeat as Ncube cuts GDP forecasts

- New perspectives: De-link politics from Zim’s education policies

Keep Reading

The primary cause of currency instability can be traced back to the central bank quantitative easing policy (money printing) to fund various quasi fiscal operations, credit exporters for retained foreign currency earnings and deficit financing of government programmes.

Unrestrained money printing is what fuels price increases and income erosion for all economic players from labour, business, and households in Zimbabwe.

The government set a month-on-month inflation target range of between 1% to 3%. There has been dismal failure in tackling inflation over the past five years. In the 2022 national budget, the forecast was that inflation would end the year below 35%.

This figure was later adjusted to 58%. Annual inflation is will close 2022 in triple digit figures and remain in that zone for at least 8 months into 2023.

Exchange rate stability

Zimbabwe has struggled with the current foreign exchange instability and misallocation since mid-2013 when foreign currency externalisation started soon after the harmonised elections.

Foreign currency losses reached alarming levels between 2014 and 2015 as alert investors discounted government treasury bills locally for foreign currency offshore after realising that the Zimbabwean dollar was on its way back and there was massive dilution of US dollar balances in local banks.

Bond notes introduction in November 2015 confirmed investor fears and the rest is now history. To achieve exchange rate stability, the government must make a tough choice of weather to fully dollarise the economy as was the case in 2009 or to continue with a dual currency economy on the condition that free-market reforms are implemented. These reforms include allowing a managed floating exchange rate, free movement of capital and currency convertibility through commercial banks.

At present, the central bank presides over a harsh foreign exchange regime where it prints electronic money (fueling inflation), yet it manipulates both the auction and interbank exchange rates.

Capital movement out of the country remains a nightmare for local and international investors, while businesses cannot convert Zimbabwean dollar income to foreign currency using the manipulated foreign exchange rate.

The dilemma for the government is that it needs the local currency and central bank money printing to fund various politically aligned programmes, while on the other hand inflation threatens government popularity and destroys any hopes for economic stability.

Power generation

The Zimbabwean government has not invested any significant capital from budgeted revenues towards power generation over the past two decades. Demand has been growing at a faster rate than power generation projects, yet Zimbabwe sits on billions worth of coal that can fund dormant or new thermal power stations. Instead, the government has allocated billions to military equipment, intelligence, foreign travel, and politically motivated agriculture subsidies.

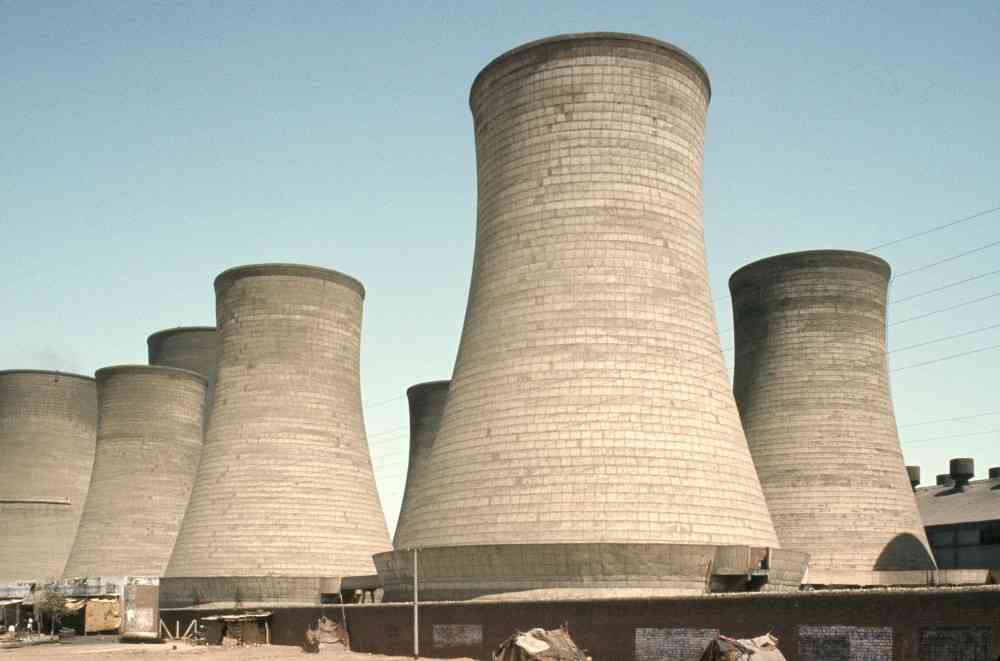

Foreign debt to support the central bank quasi fiscal operations has ballooned while power generation is downgraded to secondary priority. Zimbabwe is heavily reliant on old power stations, which have been running nonstop for decades.

Hwange Power Station was commissioned between 1983 and 1986 with installed capacity of 920MW (current output at 300MW). The station largely uses old technology from the 1960s, which leads to frequent breakdowns.

Munyati Power Station was built between 1946 and 1957 with a design capacity of 120MW but is currently producing 0MW.

Harare Power Station was built in 1942 and 1955 in phases with a maximum capacity to produce 156MW but is currently producing 0MW. Bulawayo Power Station was commissioned between 1947 and 1957 with an installed capacity of 120MW and is producing 11 MW now. External loans from China on Kariba South, Hwange 7 and 8 projects with a total capacity of 900MW remain the only investments done in power generation. This means that Zimbabwe power supply rests on rainfall patterns in order to generate maximum energy from Kariba Hydro Electric plants. Currently, power generation averages 500MW against demand of 1 700 MW during peak periods.

Demand for power is expected to eclipse 4 000MW by 2025. In 2023, the government simply needs to allocate domestic resources to thermal power stations while allowing currency convertibility for Independent Power Producers (IPPs) to secure funding and invest.

These investments are anchored by a competitive tariff and a stable foreign exchange market. In the short term, the government must allocate foreign currency to Zesa to prepay for power imports from the region to avert the power crisis in the economy.

Addressing legacy issues

Agriculture remains central to Zimbabwe’s economic revival hopes even though its contribution has declined to less than 8% of GDP in 2021. Reindustrialisation efforts are connected to agriculture revival as the sector contributes 60% of the raw materials needed in the industry.

It is now 22 years after the land reform programme and the compensation of former commercial farmers for developments done on the land is a positive gesture by the government towards normalising international relations.

However, land development or investment by resettled small scale farmers and commercial farmers is hampered by lack of title to the land. Most of Zimbabwe’s resettled farmers have no bankable title deeds which makes it worthless in asset terms and difficult to access credit from financial institutions. The issued 99-year leases are not legally transferable, hence not appealing to the banking sector in an environment where confidence and policy consistency are in short supply. The government should create a legal framework that makes the lease transferable and allow banks to hold the lease or any movable property as collateral for any credit advanced to farmers.

Apart from compelling the borrowers (farmers) to service their loans, this will uncover the country’s economic value and mitigate risk for the financiers to support agricultural production.

Without title deeds for private sector funding, agricultural productivity will remain depressed as most farmers lack capital to produce at commercial level.

Years of government funding to resettled farmers have created a vicious circle of high-level corruption that burdens the taxpayer. The government should now desist from unilateral decisions that may further infringe property rights on productive land considering that there are large tracts of underutilized and uninhabited land in the countryside.

The success of small-scale farmers in tobacco farming and the food insecurity bedeviling the country has presented a few lessons that are key in growing agricultural output going forward.

The government needs also to channel funding towards small scale irrigation equipment to allow all year-round farming and avert climate change enforced droughts.

Political stability

Economic growth is premised on political stability and market confidence. Year 2023 makes headlines for the anticipated harmonised elections to be held on or before August as stated in the constitution. Past elections have been marred by violence, vote rigging claims and electoral malpractices which have cost the local economy dearly in terms of investment.

Political instability that follows disputed elections has a negative effect on policy implementation, investor perceptions, capital movements, market confidence in government policy, economic stability, and long-term prospects.

Zimbabwe requires private sector capital for growth and that capital needs inclusive governance. The 1987 Unity Accord brought economic stability and the same can be said of the 2009 Global Political Agreement (GPA) that ushered in the government of national unity between 2009 and 2013.

Without political stability, it is practically impossible for the government to source any significant credit lines for retooling the local economy, bring market confidence for meaningful local or foreign investment, and achieve monetary or economic stability in 2023 and beyond.

In a nutshell, the government needs to prioritise the above risks that can derail economic growth in the short term while also chatting a path for long term economic development. There is need to move away from knee jerk policy interventions and intensify implementation of long term inspired economic reforms. Policy actions are urgently needed to tackle the root causes of economic instability such as money printing and to enable private-sector led economic growth.

Bhoroma is an economic analyst. He holds an MBA from the University of Zimbabwe (UZ). — vbhoroma@gmail.com or Twitter @VictorBhoroma1.