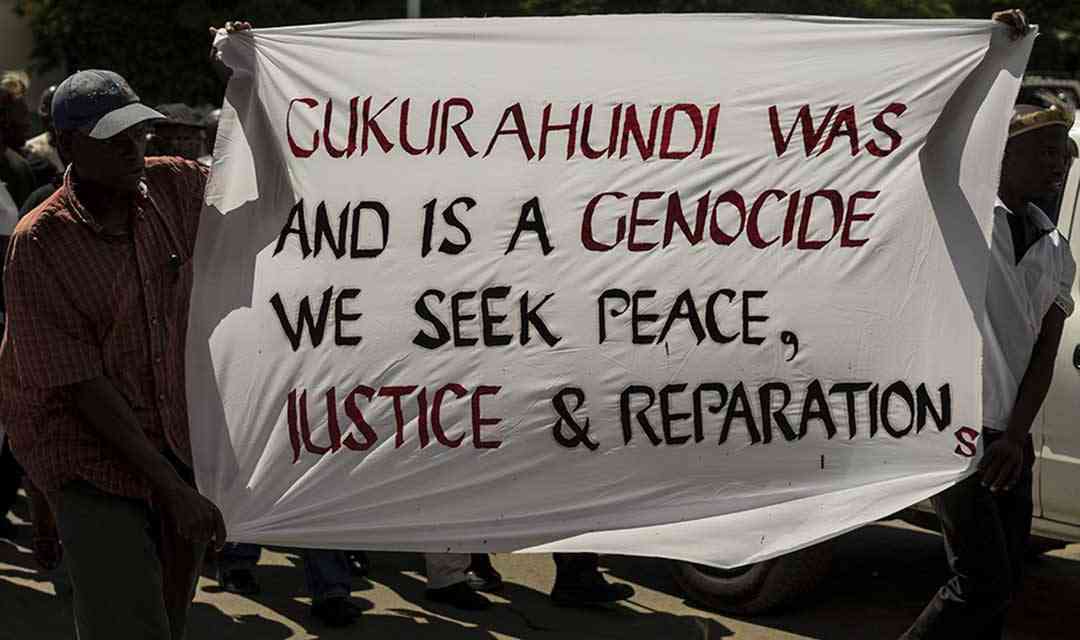

THE Gukurahundi public hearings begin today as the government seeks to find closure to the emotive issue, more than 40 years after the North Korea-trained 5 Brigade rolled into Matabeleland and Midlands provinces, leaving thousands dead, according to human rights groups.

Then, the Robert Mugabe administration said the 5 Brigade was meant to “flush out” dissidents, although critics say it was designed to pave way for a one-party State.

About 20 000 people were killed by the 5 Brigade unit in the Midlands and Matabeleland provinces, according to the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace.

The second republic should be credited for initiating the process after its predecessor did nothing, with Mugabe referring to Gukurahundi as a “moment of madness”.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa appointed traditional leaders to lead the public hearings to address the emotive issue, which remains a dark chapter in the country’s history.

However, the public hearings begin on the wrong footing. They will be held in camera. Victims and survivors are not allowed to record proceedings. The media have been barred from covering the hearings.

It means information from the hearings will come in dribs and drabs, amid fears the government intends to manage the outcome. The scepticism is justified. More than 40 years ago, the government established the Chihambakwe Commission to investigate the killings.

The report by the commission, chaired by top lawyer Simplisius Chihambakwe, has never been made public, it's gathering dust elsewhere in some office.

- Ziyambi’s Gukurahundi remarks revealing

- Giles Mutsekwa was a tough campaigner

- New law answers exhumations and reburials question in Zim

- Abducted tourists remembered

Keep Reading

This has triggered fears that the report from the hearings will gather dust like the Chihambakwe Commission report, which has not been made public since its completion over 4 decades ago.

Gukurahundi has been with us for over 40 years. It will still be a topical issue in the future if we don’t put our act together and undertake a credible process that takes into cognisance the concerns of survivors and victims.

It is not a matter of compensation, but the need to find closure to the emotive issue. And that entails getting to hear the views of the victims and survivors in a manner that allows them to open up, without fear of reprisals.

If the media is banned, they will be reserved and the public hearings will not achieve their intended objectives.

The perpetrators need to apologise so that healing takes place.

This is not a simple matter. Some families don’t know where their relatives are buried, and children were deprived of parental affection and care.

Elsewhere in the world, hearings are made public and even televised to show sincerity in the process.

It appears those overseeing the process have a predetermined outcome after brushing aside concerns of key stakeholders, including victims and survivors. It’s like a delayed match whose result is already known.

Should we bungle the process after coming this far? It has taken the government nearly 40 years to tackle this emotive issue. There is still time to tweak the process and make it transparent in the eyes of the victims and survivors. They cannot be coerced to accept a flawed process. This is the closest we have been to addressing the Gukurahundi atrocities.

We cannot not afford to squander such a golden opportunity.