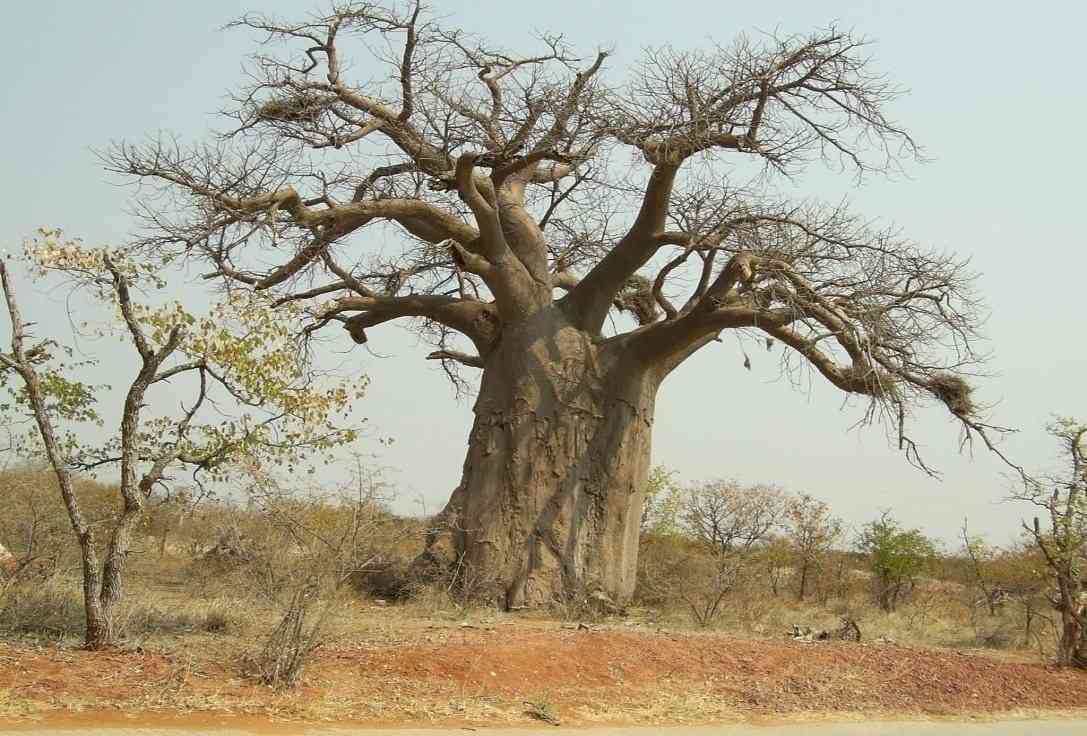

Travelling in a bumpy, dusty and potholed road in Gutu district, about 368 kilometres south of Harare, visitors are welcomed by the sound of pestle and mortar, pounding baobab fruit which is being crushed into powder.

In the early morning, the powder from the fruits smell like roasted groundnuts from a distance.

Tapiwa Marove, 41, and his wife Getrude are already up, and preparing porridge from the baobab fruits powder.

Many more families are either grinding these fruits, or doing other innovations to survive.

“We are a family of five,” Marove said.

“This year we did not harvest much from our maize fields. As you can see, we have gathered piles of baobab fruits. We will use them as our first meal of the day. This helps us to preserve the grain for much longer.

“We have already seen that if we don’t do our budget correctly our produce will not take us to the next harvest in April 2024,” Marove said.

Marove usually crushes baobab fruits for the whole week’s meals.

- Govt to distribute grain as hunger stalks millions

- Zim’s urbanites facing high prices

- 3,8m villagers face hunger

- Food crisis looms in Sadc

Keep Reading

“I usually crush the baobab fruits to get the powder, which will be very fine. We keep the fruit clean and dry, ready for use. Early in the morning my wife cooks porridge, which we eat as our first meal of the day. In the afternoon we eat other foods if we have,” he said.

“We also take the seeds and roast, grind them into powder which we use for making tea.

“They have proved to be very useful. We do not only use tea for our consumption but pack it into some small packets for sell to villagers at Nyikavanhu Growth Point and other areas like Gutu town for US$1 each. We use the money for our day-to-day needs,” he said.

Baobab fruits have also helped fight deforestation, with families using their shells as firewood instead of cutting down trees.

With the unemployment rate standing at more than 90% in Zimbabwe, where almost six million people aged 45 and below have left the country in search for greener pastures, innovations like these have helped families survive.

The majority of people of Marove’s age have crossed the crocodile-infested Limpopo River south of the country into neighbouring South Africa to escape from Zimbabwe’s biting economic hardships.

Currently the country’s inflation rate stands at 175,8%, one of the world’s highest.

“I think I have managed to make ends meet feeding my family considering that we are facing hyperinflationary and high unemployment rate. I still have hope that one day I will get a formal job that would enable me to fend for my family,” Marove said.

As the country readies for general elections on August 23, the economic crisis will be the top most in the minds of voters in deciding if they should give President Emmerson Mnangagwa and his Zanu PF party another term.

For now, Mnangagwa has failed to find solution to the country’s burning problems, and this is seen through struggles that people like Marove are going through to put food on the table.

According to the World Food Programme (WFP)’s HungerMap LIVE, approximately the four million people are facing insufficient food consumption as of February 2023.