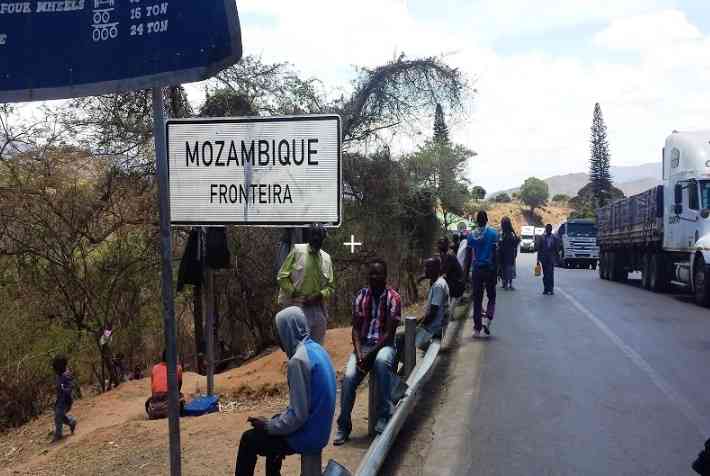

Two women approach the soldiers standing guard over Zona, an illegal crossing point between Zimbabwe and Mozambique. It’s one of three illegal crossing points around the Mount Selinda region in eastern Zimbabwe.

Although a border between the two countries exists here, a product of the 1891 Anglo-Portuguese treaty, there is nothing to indicate a demarcation or a crossing point, except the presence of soldiers and police.

The women speak momentarily to the soldiers, then they proceed on the dusty paths that lead into Mozambique.

Ordinarily, no one is supposed to cross the border at this point.

But the women have paid a fee to facilitate their crossing. It’s not a legal transaction, but so normalised that it occurs in the open. Locals say it costs about US$2 to cross in and out of Zimbabwe.

Despite official border points for regulated crossings, this illegal movement in and out of Zimbabwe along the porous border is common.

Many travel to Mozambique to buy cheaper basic commodities, such as rice, fuel and cooking oil.

Those from Mozambique cross over to buy commodities sold at cheaper prices in Zimbabwe or to seek services in hospitals and schools.

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Bulls to charge into Zimbabwe gold stocks

- Ndiraya concerned as goals dry up

- Letters: How solar power is transforming African farms

Keep Reading

It’s a strong cross-border ecosystem which has allowed border communities to navigate economic hardships brought about by the pandemic and other social and political forces that have rocked both countries.

But for Zimbabwe, this has strained the border region’s already struggling healthcare system, widened space for criminal activities and led to a bleeding over of cultural practices that can harm the environment, such as charcoal production.

The situation demonstrates the consequences of colonial borders — which remain difficult to control years after they were implemented — on local communities in both countries that share social ties through language, marriage and ancestry.

Extra strain on health care

Just a few miles from the illegal crossing point into Zimbabwe’s Chipinge district is Mount Selinda Mission Hospital.

Dorcas Mhlanga travelled 25 km to give birth. She lives in Mufudzi, a border village in Mozambique, and has crossed into Zimbabwe illegally.

“I came here because it’s nearer to my home, plus I prefer this hospital compared to the one in Espungabera in Mozambique because the services here are better,” she says.

Like most Mozambicans who now seek healthcare services in Zimbabwe, particularly at Mount Selinda Mission Hospital — the only major hospital in this border region — Mhlanga is hesitant to confirm her nationality. If she does, she worries the hospital will charge her more in maternity fees.

“Even when our family members get sick, they come here for treatment,” she says.

Tension and unrest across Mozambique, which resumed in 2013 between the Mozambican National Resistance Movement and government forces, has put a strain on the country’s economy, weakening its systems, including health care infrastructure, according to the World Health Organisation.

Less than half of Mozambique’s population has access to healthcare services, with just three doctors for every 100 000 people.

But in Zimbabwe, the economy is declining and systems are similarly strained. Public hospitals, once robust in the 1980s, now lack equipment and medicines, as well as trained and motivated health professionals.

Lovemore Sithole, medical superintendent at Mount Selinda Mission Hospital, says that almost one-third of the patients the hospital treats come from Mozambique, burdening the border region’s health sector. “Economically we are inseparable.”

To stay operational, the hospital relies on patient fees, Sithole says.

“But these are very small because most of the services are free.”

The hospital also receives support from the Ministry of Health and Child Care, which disburses funds based on the recorded population of Zimbabweans in the area, and even that is barely enough to serve the current population of around 15 000 Zimbabweans in the area, Sithole says.

Despite the strain, the hospital provides health care to those who seek its services, whether they are Zimbabweans or not. They are a church institution, Sithole says, and can’t turn people away.

The situation extends back to the colonial period, says Francis Dube, a scholar of public health in this region and associate professor of history at Morgan State University in the United States.

Dube, in a written response, says that during the colonial period, Zimbabwe had a more robust healthcare system than central Mozambique. Africans on the Mozambican side of the border frequently sought healthcare services in Zimbabwe, and Portuguese officials in Mozambique, which was a colony of Portugal, regularly issued permits to Mozambicans to seek healthcare in Zimbabwe.

Although there isn’t much recorded data to capture the current scale of patients coming from Mozambique to Zimbabwe for health care services, past studies show the influx can be massive.

Local health clinics saw a surge in patients in 2016, for example, after thousands fled the conflict between the MNR and the Mozambique government to find refuge in Chipinge.

Before the influx, the Mabee clinic in Chipinge served about 900 patients a month, but that number spiked to between 2 000 and 3 000 a month after the conflict began, overwhelming the clinic, according to a report by the Chipinge District Civil Protection Committee.

Simon Nyadundu, Manicaland provincial medical director, where the hospital is located, didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Rustling and smuggling on rise

The porosity of the border has also fueled cross-border criminal activities. Locals and authorities say that cattle rustling and smuggling have become more rampant.

Cattle are easily herded to Mozambique and illegal goods are easy to transport in and out of Zimbabwe.

Fungai Sithole Mananga has been a casualty of livestock theft. He had left home in 2021 to look for employment in Johannesburg, South Africa, when he received word that his two cows had been stolen.

“My wife told me that they had followed the footprints of the cows and discovered that they had been transported through the porous border points,” he says.

Andrew Masheedze, headman for Masheedze village in Mount Selinda, says many people have fraudulently acquired identity documents for both countries, which makes it difficult to trace criminals.

Masheedze has also had cows disappear from his kraal, an enclosure for livestock.

“I traced the footprints of my cows from my kraal across the Zona border post,” he says. He never found them.

Illegal commodities are also easy to smuggle into Zimbabwe. For example, the Zimbabwean government mandates that fuel sold to motorists be blended with ethanol. But some motorists prefer regular unleaded fuel as it lasts longer. It’s possible to purchase this fuel in Mozambique and sell it in Zimbabwe, says an attendant at a fuel station in Mount Selinda who asked to remain anonymous for fear of losing her job.

Tadious Ngadziore, Ward 19 councilor in Mount Selinda, decries corruption at the border.

“Those who are supposed to guard the border sort of legalise the illegal crossing of people by asking for bribes,” he says.

But the police face some challenges, he adds. It’s difficult for authorities in Zimbabwe to investigate a crime once the perpetrators cross the border.

The police in Zimbabwe are aware of the situation, says assistant police commissioner Paul Nyathi, and have been conducting investigations. They’ve arrested several people who were smuggling goods into the country and attempting to bribe border officials. They also have carried out a special operation, “No to Cross-Border Crimes,” which has proven successful in bringing those involved to account, Nyathi says.

The Embassy of Mozambique in Zimbabwe didn’t respond to requests for comment.

- Mujuru is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Harare, Zimbabwe. She specialises in reporting on agriculture and the economy. Linda has worked as the programme manager for Media Centre Zimbabwe, where she supported journalists across the country.