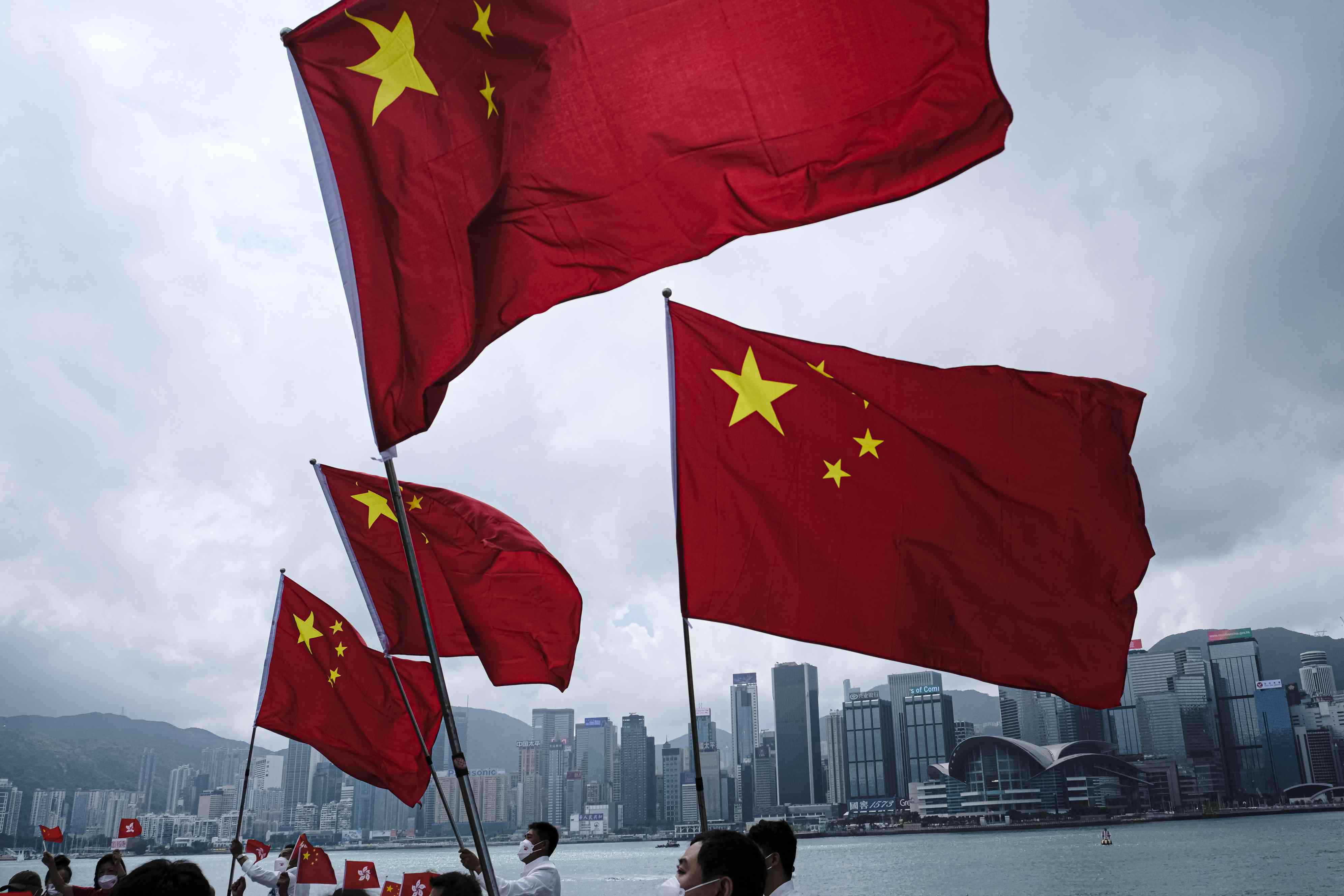

GENEVA: This month marks ten years since the Chinese government launched an unprecedented crackdown on human rights lawyers and legal activists, a campaign that rights groups say has fundamentally reshaped the country’s legal landscape — not through reform or progress, but through fear, repression, and the systematic dismantling of independent legal advocacy.

What began on July 9, 2015, with the detention of over 200 lawyers, legal assistants, and activists, has evolved into a relentless campaign that continues to reverberate through China’s judicial and civil society apparatus.

Human rights groups around the world — including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the International Commission of Jurists — have renewed calls for an international investigation into what they describe as “a decade of systematic repression.”

The movement, now known widely as the “709 Crackdown” — a reference to the date it began — was ostensibly aimed at curbing legal professionals who challenged state authority or advocated on behalf of politically sensitive clients.

These included victims of land seizures, religious minorities, democracy activists, and others marginalised or targeted by the state.

But the 709 campaign was never limited to a single event or isolated to one moment in time.

Rather, it marked the beginning of a broader shift under President Xi Jinping, wherein the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sought to reassert ideological control over all aspects of civil society — particularly the legal profession, which had, in the decade prior, become an increasingly active site of advocacy, dissent, and public accountability.

Targeting the rule of law itself

- The brains behind Matavire’s immortalisation

- Red Cross work remembered

- All set for inaugural job fair

- Community trailblazers: Dr Guramatunhu: A hard-driving achiever yearning for better Zim

Keep Reading

Unlike previous waves of political repression in China, which focused primarily on dissidents, journalists, or religious groups, the 709 Crackdown went after the very intermediaries of the legal system — the lawyers who took up “sensitive” cases and sought to defend people using the law itself.

Lawyers such as Wang Quanzhang, Yu Wensheng, and Li Yuhan were disbarred, disappeared, imprisoned, or otherwise silenced.

Legal firms that were known for rights-based defence work were shut down or had their licenses revoked.

Some detainees, such as Xie Yang and Jiang Tianyong, later recounted experiences of forced confessions, prolonged solitary confinement, and psychological torture — allegations the Chinese government has routinely denied, dismissing them as “fabrications” by “anti-China forces.”

The chilling message sent across the legal profession was unmistakable: lawyers were not above the political line. Advocacy for human rights, particularly when it clashed with Party priorities, would not be tolerated — even if it was done through legal channels.

Legal institutions as instruments of control

What makes the crackdown especially insidious, according to rights monitors, is how it co-opted the very institutions meant to uphold justice.

Courts, bar associations, and prosecutorial bodies became instruments of political enforcement rather than guardians of legal neutrality.

State-run bar associations issued disbarment notices with little transparency or due process.

Lawyers were surveilled, their families harassed, and in many cases, their children were barred from attending school.

The crackdown extended to legal education as well, with law schools instructed to emphasise “political reliability” over legal integrity.

Chinese officials continue to defend these actions as necessary to protect “social stability” and guard against “hostile foreign forces” exploiting the legal system.

But international observers view this rationale as a pretext for authoritarian consolidation.

Expanding the repression playbook

While the early years of the crackdown targeted lawyers known for public interest work, the net has since widened.

In recent years, corporate lawyers, academics, NGO staff, and even student activists have faced pressure for expressing views that deviate from the Party line.

Notably, many lawyers who have attempted to continue rights-based work after release from detention have reported continued surveillance and restrictions on their movement.

Several have disappeared altogether, with the government offering no information on their whereabouts.International human rights experts have raised the alarm about the normalisation of such tactics.

The United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances has repeatedly called on Beijing to reveal the fates of missing lawyers.

Meanwhile, the European Union and the United States have condemned the crackdown, often tying it to broader concerns about the rule of law and transparency in China.

Yet Beijing has remained largely unyielding. Officials often portray rights lawyers as provocateurs bent on undermining national unity or as puppets of Western governments — accusations echoed in state media campaigns designed to discredit not just individual lawyers, but the very notion of adversarial legal defence.

The toll on China’s civil society

Perhaps the most enduring impact of the crackdown has been the climate of fear it has instilled across civil society.

In the years since 2015, fewer lawyers have been willing to take politically sensitive cases.

Many legal professionals now self-censor, avoiding issues involving religion, land rights, labour disputes, or anything deemed “politically sensitive.”

Independent NGOs, once key collaborators with rights lawyers, have seen their operations curtailed under the Foreign NGO Law of 2017 and other restrictive measures.

The space for civil discourse has narrowed dramatically, as political red lines increasingly circumscribe legal representation.

Family members of detained lawyers — particularly wives and children — have become de facto activists themselves, drawing international attention to abuses through press conferences, letters, and social media campaigns.

Some have even faced travel bans or surveillance as a result.

Li Wenzu, the wife of Wang Quanzhang, became a symbol of quiet resistance as she campaigned for her husband’s release.

A legacy of repression

Ten years on, the legacy of the 709 Crackdown is unmistakable. It shattered the fragile hope that China’s legal system might evolve toward greater independence.

Instead, it confirmed the CCP’s determination to subordinate law to politics, undermining any pretence of judicial autonomy.

While a handful of high-profile cases have drawn international headlines, hundreds of lesser-known lawyers and legal activists remain detained, disbarred, or in hiding.

The long-term consequence is a legal profession that, according to many observers, has been cowed into submission.

And yet, rights groups insist that memory is a form of resistance.

Their calls for an international probe are not merely symbolic. They reflect an effort to keep alive the stories of those who dared to defend others — not with weapons or slogans, but with laws, constitutions, and courts.