KAMPALA, UGANDA — It was around 9 a.m. when Mwesigwa Masagazi heard what he thought were gunshots. He was at work on a January day this year, building a water drain in a village near his home. A few minutes later a friend called him.

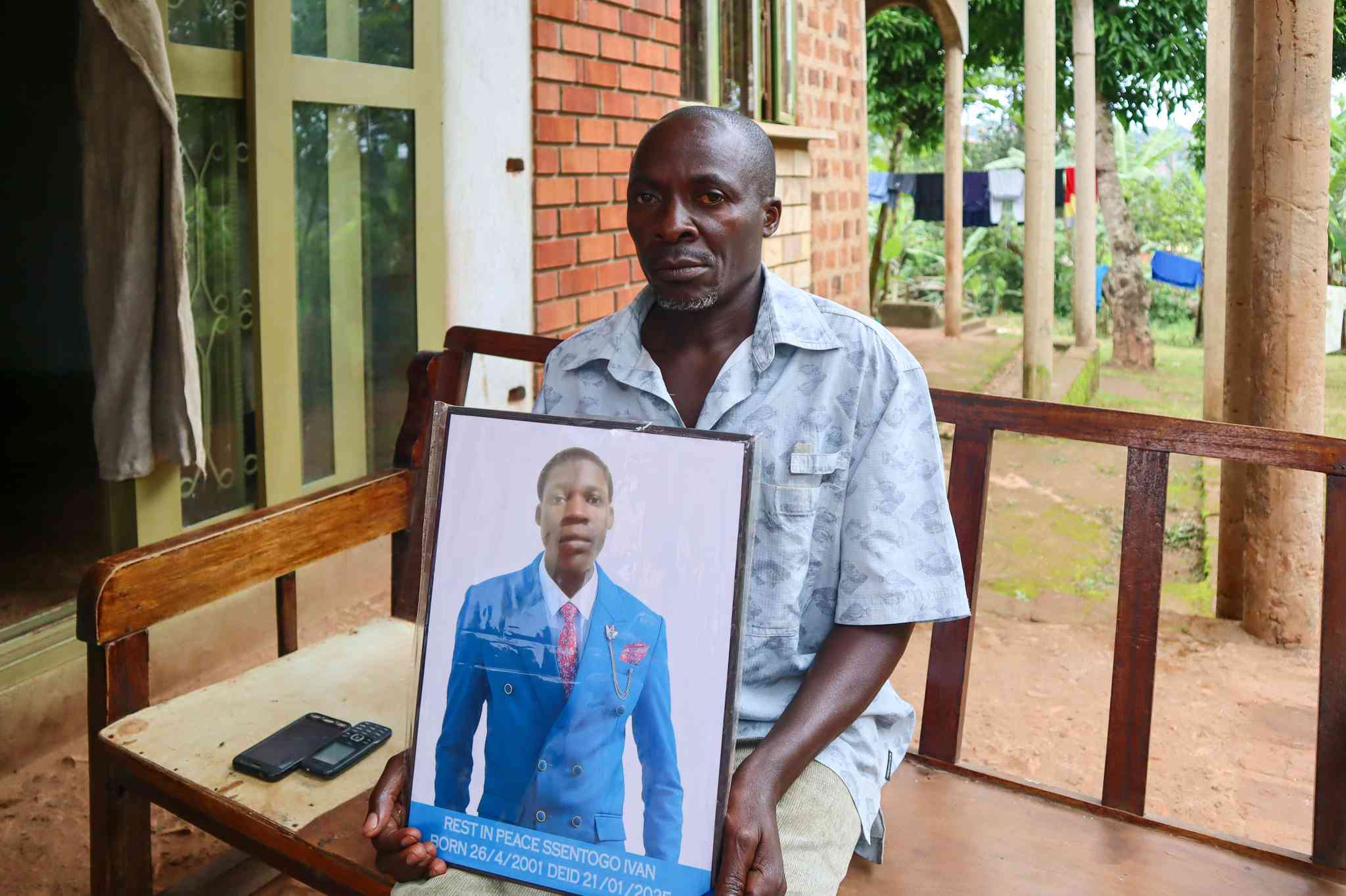

“Ivan is dead,” the caller said. Masagazi thought it was a prank. He had seen Ivan Sentongo, his son, two hours earlier at home. How could he be dead?

Masagazi immediately left work and rushed to the spot where his son had been shot, only about 150 meters (less than 500 feet) away from where Masagazi had been working. There, lying prone on the ground, in pools of blood, was 23-year-old Sentongo, lifeless. His body was surrounded by more than a dozen people, including about 20 soldiers from the army, the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces.

Masagazi asked an army officer why his son had been killed. The officer did not respond. It was only days later, in a police report that Masagazi tracked down, that he

learned that his son had been shot and killed while supposedly attempting to rob someone. The police report didn’t specify the time Sentongo was killed.

“Something didn’t add up. My son was killed in the broad daylight, in the morning, after he had just bought a kindazi [a snack],” Masagazi says, almost in a whisper.

Masagazi says the child from whom Sentongo bought the snack told him that his son raised his hands when he was approached by three UPDF soldiers who pointed a gun at him and then shot him.

Masagazi believes his son was the target of an extrajudicial killing, which many in Uganda say is a constant concern.

- Revisiting Majaivana’s last show… ‘We made huge losses’

- Too young to marry: The secret world of child brides

- Edutainment mix: The nexus of music and cultural identity

- ChiTown acting mayor blocks election

Keep Reading

“If my son was indeed a thief as they claim, they should have arrested him and taken him to police. But killing him in broad daylight, unarmed, is horrifying,” he says.

A regular occurrence

Extrajudicial killings are executions of people by state authorities without due process, or any fact-finding that might point to guilt. They have shown no sign of abating in Uganda, according to nongovernmental organizations and others who track them. While there is limited data about the frequency of extrajudicial killings in Uganda, human rights observers say they occur regularly, in violation of law and Uganda’s Constitution.

Henry Byansi, a human rights lawyer with Chapter Four, a local nonprofit, and others believe there have been hundreds of extrajudicial killings in Uganda, usually by members of the army but at times by the police. There are seemingly endless delays in the criminal justice system, leaving the people alleged to have conducted these killings unaccountable for their actions.

The police, meanwhile, deny there’s a problem.

“In Uganda we don’t have extrajudicial killings. … I have not heard of any police officer participating in extrajudicial killings,” says Patrick Onyango, Kampala Metropolitan Police spokesperson. He adds that there are times when police officers in the line of duty unintentionally kill somebody with a stray bullet.

Col. Chris Magezi, acting spokesperson for the army, says he is unaware of any extrajudicial killings and that civilians killed are those engaged in violent crimes.

Scarce data, ongoing killings

Though advocates say extrajudicial killings are ongoing, recent data is scarce. During the two-year period between 2016 and 2018, 133 such killings were carried out by the army and the police, according to a 2019 study by the Human Rights and Peace Center at Makerere University School of Law. (This data does not include the more than 150 people, including children, killed in a 2016 attack by the Ugandan government on the Rwenzururu Palace and government offices of the traditional Rwenzururu kingdom.)

Zahara Nampewo, deputy dean at the School of Law at Makerere University and former executive director of its Human Rights and Peace Center, believes there are many more extrajudicial killings than researchers are able to document. She says there are many instances of people mysteriously disappearing only to have their bodies found later.

And there are well-known recent instances, as well.

A week before Sentongo’s killing, the police shot and killed four robbery suspects who they said intended to rob a bank at Acacia Mall in Kampala.

Kahinda Otafire, Uganda’s minister of Internal Affairs, later told legislators that “under no circumstances should a Ugandan be executed or killed when he is in handcuffs or

… unarmed.” In the same session, Abas Byakagaba, the inspector general of police, assured legislators that there would be a thorough investigation of the deaths.

Hassan, the brother of Katongole Fahad, one of the four people killed by police at the mall, is unconvinced that justice will be done. He asked to be identified by only his first name for fear of harassment.

“Those are words we have heard before from government, but the trend seems to increase over the past years,” he says, adding that he’s heard eyewitness accounts that say some of the suspected robbers were killed with their arms raised in surrender or as they ran from the scene. Others, he says, were killed laying with their faces on the ground.

Hassan says his brother’s head had a bullet hole in the back, leading him to believe that he was shot from behind, with his face down.

Onyango, the police spokesperson, says what transpired that day at the mall was not extrajudicial killings, but part of an effort by police to stop “guilty criminals” with a history of committing aggravated robbery who had been tracked by police after they had left jail on bail.

Onyango also says that one or two of the suspected mall robbers may have been innocent. The investigation is continuing, he says.

Growing militarization

Nampewo, the law school dean, says the country’s growing militarization — with the military involved in everything from land deals to fisheries — has threatened the rule of law and caused the public to have less trust in security forces.

“Over 40 years we have been talking about a professional army that should be able to disarm. … But what we see is the militarization of many sectors and use of extreme force used against civilians by the armed forces, including suspects of robbery,” she says.

Violence at the hand of Uganda’s military is nothing new. The 2016 conflict at the Rwenzururu Palace is a prime example of the problem, human rights experts say.

Government forces stormed the kingdom’s palace and killed 153 civilians, according to Human Rights Watch. The report described what is known as the Kasese Massacre. Amnesty International condemned the killings soon after they occurred. Amnesty’s East Africa researcher, Abdullahi Halakhe, labeled the deaths “extrajudicial executions” and “unlawful killings.”

“During the scuffle, what strength did women and children who were killed, women who were undressed, have against the army?” Nampewo says.

Magezi, the acting spokesperson for the army, says those killed in the 2016 palace massacre were part of an anti-government militia. He also questions the accuracy of the 2019 report from Makerere University’s Human Rights and Peace Center about extrajudicial killings.

“Did they account for over 20 police officers who were killed in Rwenzururu and three UPDF soldiers?” he asks.

A new rule of law

The government and its law officers are not committed to ensuring that extrajudicial killings come to an end, says Byansi, the human rights lawyer. Instead, he says, they substitute their own actions for a court decision.

“They are the ones who sanction these operations so they are aware and fully understand who poses the gun and at which operation,” Byansi says. “The excuse of them still doing investigations is just a signal that they are not willing to have these people prosecuted because they are on the mission that benefits them.”

Some lawmakers agree. People are worried about crime, but “the police investigative agencies … do seem not to do a good job sometimes,” says Yusuf Nsibambi, a member of Parliament.

Masagazi, meanwhile, says that only justice and transparency about his son’s death can bring him any hope of ending extrajudicial killings of civilians.

People need to be held accountable, he says. The military holds the guns, he says, and that “is ruining this country.”

Nakisanze Segawa is a Reporter-in-Residence based in Kampala, Uganda. She specializes in reporting on LGBTQ+ issues. Born in Luweero and raised in Uganda’s capital, she holds a degree in Mass Communications from Muteesa I Royal University. Known for her powerful photography and deep community access, her 2015 story about school policies that forced Black girls to keep their hair short—while girls of other races could grow theirs long—provoked widespread social media outcry and led to a policy change.

Nakisanze Segawa, GPJ, translated some interviews from Luganda.

This story was originally published by Global Press Journal