BY BRENNA MATENDERE A scramble for Zimbabwean chrome by Chinese miners has left a trail of destruction on the environment along the Great Dyke where abandoned pits are posing a deadly threat to human life and livestock.

Increasing demand for chrome on the international market has spurred a rush by both local and Chinese companies to set up operations to mine the sought after mineral in some Midlands districts.

Zimbabwe boasts the world’s second largest chrome reserves behind South Africa.

Chrome is a blackish mineral used in the production of stainless steel. The product is in demand in Asia, particularly in China and Singapore.

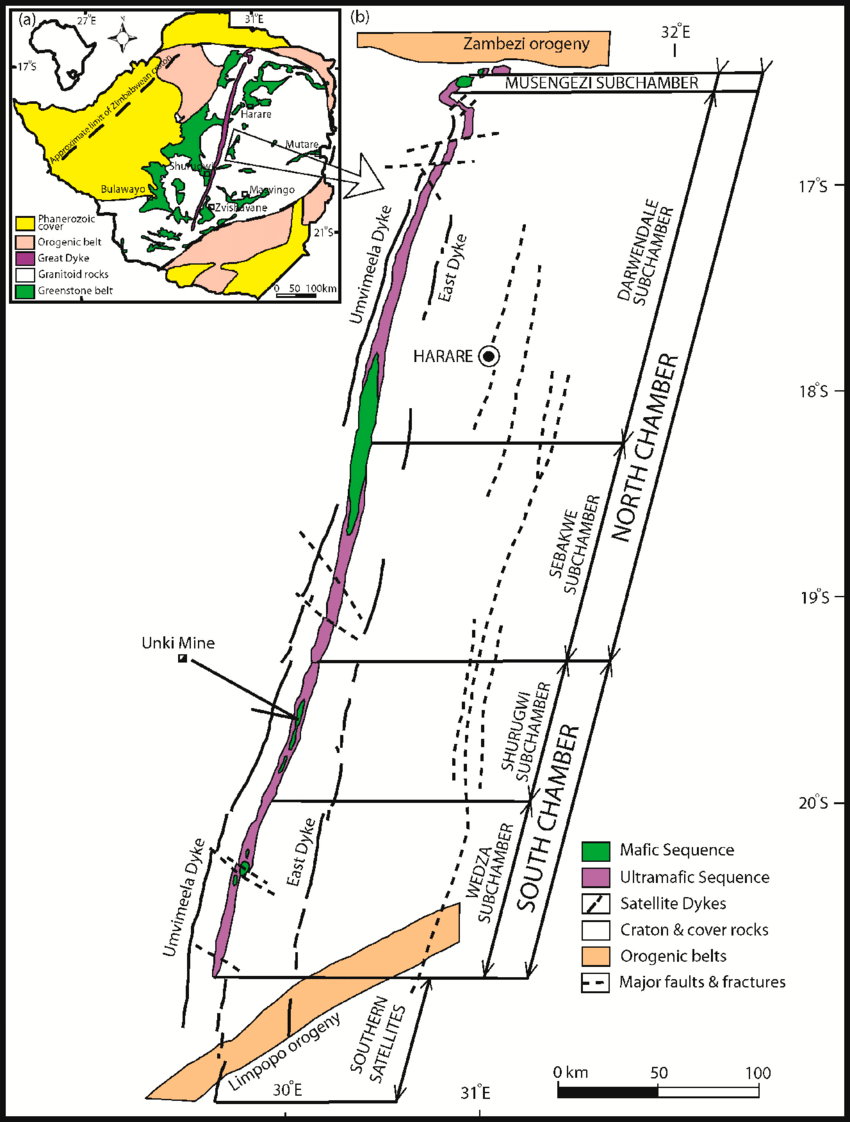

Most of the chrome mines are dotted along the Great Dyke, a narrow series of long, low ridges and hills stretching for about 515km from near Harare into the Midlands.

Some of the minerals found in the Great Dyke include chrome, gold, silver and platinum.

Small-scale chrome and gold miners use some of the most rudimentary techniques that include digging open pits that they abandon after exhausting the mineral deposits.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Investigations by The Standard in collaboration with the Information Development Trust (IDT), a non-profit organisation that supports journalists in Zimbabwe and southern Africa to investigate issues of corruption in the public sector and bad governance, revealed that the chrome mining activities have caused irreparable damage to the environment, especially in Shurugwi, Zvishavane and Mberengwa.

Some of the pits were abandoned as far back as 20 years ago and this has put the lives of villagers and their livestock in danger.

Offenders range from local small-scale miners contracted by Chinese middlemen to the country’s ferrochrome giants — Zimbabwe Mining and Alloy Smelting Company (Zimasco) and ZimAlloys.

The Chinese have a major shareholding in Zimasco while ZimAlloys had a partnership with a Chinese firm that ended last year, but the company still exports large quantities of chrome to the Asian country.

Sinosteel Corporation, China’s second largest iron ore trader, has a 73% stake in Zimasco, which it acquired in 2007, according to the Asian country’s National Development and Reform Commission.

On the other hand, ZimAlloys entered into a partnership with Chinese based company, Jinan in 2014.

The investor reportedly invested US$2,3 million into the partnership and set targets to produce four million tonnes of chrome ore annually.

Alongside the small-scale miners, Zimasco and ZimAlloys, are accused of scarring the land that poor villagers rely on for cultivation of crops and rearing of domestic animals.

A 2013 report by Parliament’s portfolio committee on mines and energy noted that some of the chrome mining claims that were in the hands of indigenous players in the Great Dyke were “in reality owned by Chinese companies”.

“These are being used as fronts by Chinese companies,” reads part of the report.

“Of the seven Chinese miners that the committee met, only one confidently admitted that it had acquired the claims through the proper channels.

“The (Minerals Marketing Corporation of Zimbabwe) MMCZ also confirmed to the committee that one of its audits revealed that there were some locals, who were being used as fronts by Chinese to acquire claims.”

Of the seven Chinese companies mining chrome in the Great Dyke, only one was able to confirm to the committee that it had adequate documentation legalising its operations in the country.

“The rest of the companies were evasive on how they acquired legal authority to operate in the country,” the report says.

The committee said the Chinese companies had an “attitude of being untouchable and could operate above the law.”

“The Chinese created the impression within the community and in some government institutions that they were protected by someone in a very high office in government,” the report added.

“As a result (the Environment Management Authority), the local authorities and the community are powerless to enforce or demand compliance of environmental and mining regulations.”

This has seen mining companies abandoning the badly damaged mining sites after ignoring mining regulations that require them to rehabilitate pits once the mining ceases.

Their footprints are very visible at Ruchanyu village nestled between Shurugwi and Zvishavane. Pits as deep as 380 metres can be seen from the Zvishavane-Shurugwi highway.

It is the same situation at Bvoora village located about 15km from Ruchanyu where huge boulders were left positioned precariously close to villagers’ homesteads.

At Bvoora this publication counted 23 pits that were left abandoned by an unnamed Chinese miner.

Four kilometres from Mapanzure shopping centre in Zvishavane district there are also numerous open pits that have been abandoned.

Mercy Chihambakwe, a villager from Bvoora, said she lost two herd of cattle that fell into the pits while a neighbour lost three goats that were never recovered.

“The pits pose a great risk especially to us women and livestock,” Chihambakwe said.

“Personally, I lost two steers that fell into the pits and we had to slaughter them because they were badly injured.

“My neighbour lost three or so goats that fell into the pits and he could not retrieve them.”

Rosemary Manyika (28) from Ruchanyu said what made her angry was that the Chinese miners just scooped chrome from their community and left them with open pits.

“They could have built a clinic or a waiting mothers’ shelter to accommodate pregnant women that live far from health centres,” Manyika said.

“Even a small school would have helped us, but nothing came from the Chinese despite having extracted loads of chrome from our area. Now they are gone.”

Dougson Shoko from Neta Village in Mberegwa blames the death of six of his family members in a car accident last year on an unnamed Chinese chrome miner, which he says left roads in the area badly damaged.

Shoko’s relatives were driving from Bulawayo to Mberengwa when the driver failed to navigate the degraded road and the car hit a tree, killing all six passengers on the spot.

“The company has no distinct name. It’s just a group of Chinese nationals, who employed locals to prospect for chrome,” he said.

“We did not get compensation from the Chinese company because their local employees did not cooperate with us.”

Locals named the mine “PamaChina”, meaning at the Chinese place. At the site there were only local workers and efforts to identity the Chinese owners drew blanks.

Other Chinese companies accused by locals of being behind the land degradation include Jinan and Almed, an amalgamated entity as well as Xi Yu.

These companies have established smelting plants in Gweru’s light industries.

In January 2013, the late Sheunesu Mpepereki who was the EMA chairperson said Chinese chrome miners in the Neta area were “breaching environmental laws willy-nilly.”

Mpepereki said the companies would be summoned before the EMA board “for causing severe land degradation in local villages”, but there is no record of that hearing ever taking place.

David Xuegong Zhou, Jinan and Almed’ group CEO, said allegations that they were responsible for land degradation in the Midlands were not true as they were not involved in any mining.

“I don’t understand what you mean. Jinan (are) smelters and are not into mining,” Zhou said.

He did not respond to follow up questions.

Kudakwashe Titus Chitakure, a human resources officer for Xi Yu who is based in Gweru, said they only bought ferrochrome from small-scale miners and they were not involved in the actual mining.

“We just buy ferrochrome ores from miners who are from surrounding areas,” Chitakure said. “We don’t mine, so we can’t cause land degradation.”

EMA admitted that the scramble for chrome had led to serious environmental degradation in the Midlands.

EMA said the unsustainable chrome mining along the Great Dyke was mainly driven by the lifting of the ban on chrome exports, rising prices for the mineral on international markets and the increased number of chrome washing and smelting plants in the Midlands.

The agency said there were some miners that were found operating “outside the legal requirements and environmental best practices along the Great Dyke”.

“In addition, there are unrehabilitated pits, which were left some 20 years back, leaving a negative environmental legacy,” EMA spokesperson Amkela Sidange told The Standard.

“Law enforcement through monitoring operations and environmental audits for (environment impact assessment) EIA certified projects were done and are still being done targeting chrome mining companies, both legal and illegal operations, with focus on rehabilitation and environmental best practices.”

The two ferrochrome giants Zimasco and ZimAlloys did not escape the EMA dragnet as they were forced to rehabilitate swathes of land where they were operating from last year.

“During the year 2021, 31 tickets and 25 environmental protection orders were issued to Chinese companies, Zimasco and Zimalloys for various offences and environmental remedial actions, which saw approximately 475ha being rehabilitated,” Sidambe added.

“In addition, two dockets were opened for implementing a mining project without an EIA certificate.

Clara Sadomba, the Zimasco spokerson, said in 2016 the firm ceded about half of its claim blocks to the Mines and Mining Development ministry in various areas, including Shurugwi and the South Dyke area.

Sadomba said the blocks were parceled out to individuals and companies, who proceeded to carry out extensive mining activities, but there were perceptions that some of the mining operations were owned by Zimasco.

“Zimasco is not the only entity with claim blocks on the Dyke, including in the specific Shurugwi and South Dyke area,” she told The Standard.

“There are several other individuals and entities with claim blocks in the same area.

“The ceded claim blocks are now owned by other individuals and entities, and most of them have been extensively mined by these new owners since the time they were ceded.

“Unfortunately, there remains some misconception that Zimasco continues to own all these areas.”

ZimAlloys spokesperson Christopher Watadza requested questions in writing when contacted for comment.

Watadza, however, did not respond to the questions and repeated attempts to contact him were fruitless.

Environment, Climate Change, Tourism and Hospitality Industry deputy minister Barbara Rwodzi, although acknowledging that some chrome miners were flouting regulations, denied accusations that Chinese companies were being allowed to operate with impunity.

Rwodzi said land degradation had occurred in Shurugwi, Zvishavane and Mberengwa areas “due to the method of chrome mining, which is open cast.”

She said in January this year, EMA amended conditions for the granting of the environment impact assessment (EIA) certificate to prohibit the buying of chrome for purposes of processing, smelting and washing from unregistered claims.

“The agency is continuing with law enforcement through monitoring inspections to ensure compliance as well as engagement of stakeholders and claim holders such as Zimasco and ZimAlloys to ensure rehabilitation is done during and after mining,” Rwodzi said.

“Various measures and strategies are being explored to ensure sustainable chrome mining where continuous rehabilitation is undertaken with strict adherence to the approved environmental management plans.

“EMA will remain resolute and steadfast in the fight against unsustainable mining activities.”

Chinese companies, especially in mining, have of late come under fire for disregarding local regulations leading to extensive damage to the environment amid accusations that authorities pay a blind eye to the violations.

On February 18, the Chamber of Chinese Enterprises in Zimbabwe (CCEZ) issued an appeal to investors from the Asian country “to protect Zimbabwe’s natural environment and historical and cultural heritage.”

🔵Small-scale chrome and gold miners use some of the most rudimentary techniques that include digging open pits that they abandon after exhausting the mineral deposits. pic.twitter.com/c5joUCBrT3

— The Standard Zim (@thestandardzim) March 16, 2022

CCEZ was responding to mounting complaints about some Chinese mining companies in Zimbabwe, who are accused of displacing locals and encroaching into ecologically sensitive areas like game reserves, to set up mining operations.

“Mining companies should conduct their operations in compliance with the law and take timely, necessary restorative measures for the environment,” the Chamber said before appealing to the Zimbabwean authorities to be “more robust” in the assessment of risks to the environment posed by mining projects.

Farai Maguwu, Centre for Natural Resources Governance director, said the Chinese miners were doing as they pleased in the Midlands because President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s government had no appetite to rein them in.

“The fact that the head of State and government, who took an oath that he will be faithful to Zimbabweans, uphold and defend the constitution and all other laws of the land is silent (about the damage to the environment) tells you where the problem lies,” Maguwu said.

“This is the time for the president to defend Zimbabwe’s sovereignty and heritage against this apparent later day colonialism.”

James Mupfumi, director Centre for Research and Development, a civic society organisation that monitors exploitation of natural resources in Manicaland, said the situation in the Midlands mirrored developments at the Marange diamond fields.

A Chinese diamond miner operating in Marange is at odds with the surrounding communities over its alleged flouting of labour laws and discrimination of locals.