When Chinese President Xi Jinping recently met the Beijing-appointed Panchen Lama, it was meant to be more than a photo op. Beijing sought to send a calculated message that Beijing, not Tibetan Buddhists, will decide the future of Tibetan religion. For the Tibetan people and followers of Tibetan Buddhism worldwide, this assertion is not only illegitimate but profoundly offensive.

By promoting a state-approved Panchen Lama and calling for the continued “Sinicisation” of religion, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is preparing the ground for an audacious move of handpicking the next Dalai Lama.

To understand the magnitude of the issue, one must first grasp how Tibetan Buddhism actually identifies a Dalai Lama. Traditionally, after the passing of a Dalai Lama, senior monks embark on a spiritual and empirical search for his reincarnation. This process involves visions, signs, rituals, and community consensus, none of which are state-sanctioned or government-controlled.

The CCP’s version, however, is radically different. Since the 1990s, Chinese authorities have insisted that all reincarnations of Tibetan lamas must be approved by the government. In 2007, they formalized this in law with “State Religious Affairs Bureau Order No. 5,” which criminalizes unauthorized reincarnations. This bureaucratic decree effectively allows atheistic party officials to override centuries of religious tradition in the name of stability and unity.

Yet, what legitimacy does an avowedly atheist government have in deciding spiritual matters?

China frames its intervention as an act of cultural preservation, often arguing that it is protecting Tibetan Buddhism from fragmentation or Western interference. But this narrative mask a more uncomfortable truth of Beijing’s intent to neutralize a ‘political’ threat.

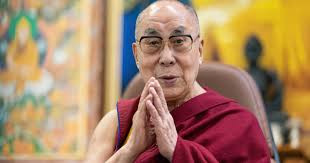

The Dalai Lama, currently living in exile in India, remains a symbol of Tibetan identity and resistance. Despite advocating for autonomy rather than independence, he is viewed by Beijing as a separatist. Installing a state-approved Dalai Lama would give China a docile, controllable figurehead; a spiritual puppet whose authority would be imposed rather than earned.

This has already played out once. In 1995, after the Dalai Lama identified a young boy named Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the reincarnation of the 11th Panchen Lama, the second-highest figure in Tibetan Buddhism. Chinese authorities detained the child and replaced him with their own candidate with Gedhun not being seen since then.

- China: The 30-year rule

- China media plays down COVID severity as WHO seeks detail on variants

- World View: How to avoid a war with China

- TikTok used for disinformation campaign in Taiwan

Keep Reading

China wants to repeat this model with the Dalai Lama: replace a spiritual leader with a compliant figurehead. However, no matter how carefully managed the process, the outcome will not be accepted by the Tibetan people or by most Buddhists around the world.

The current Dalai Lama has made it clear that no one, especially not the Chinese state, can decide his reincarnation. He has even suggested that the institution may end with him, or that the next Dalai Lama may be born outside Tibet, beyond Beijing’s reach and most likely in a ‘free country’.

Global Implications

The question of the next Dalai Lama in any case is not just a Tibetan issue but also a global one. Millions of Buddhists across the world recognize the Dalai Lama as a moral and spiritual leader. For China to unilaterally appoint his successor is not only to trample on Tibetan sovereignty but to insult the integrity of global Buddhist traditions.

Moreover, allowing the Chinese state to define legitimate religious authority sets a dangerous precedent, one that extends far beyond Tibetan Buddhism. If unchallenged, it will reinforce a model where authoritarian states can define, co-opt, and control religious institutions to serve nationalist agendas.

In matters of religion and tradition, legitimacy is not about legality or state power. It is about recognition, faith, and authenticity, none of which can be manufactured by decree. The Chinese state’s attempt to impose its will on a deeply spiritual process is a violation not just of Tibetan autonomy but also of the separation of religious matter and state affairs.

When the time comes, the world will have a choice; to either recognize the successor named by the Tibetan community and their spiritual leaders, or to accept a state-appointed figurehead lacking both credibility and moral authority. For anyone who believes in religious freedom, cultural dignity and the right of a people to preserve their traditions, the choice should be clear.