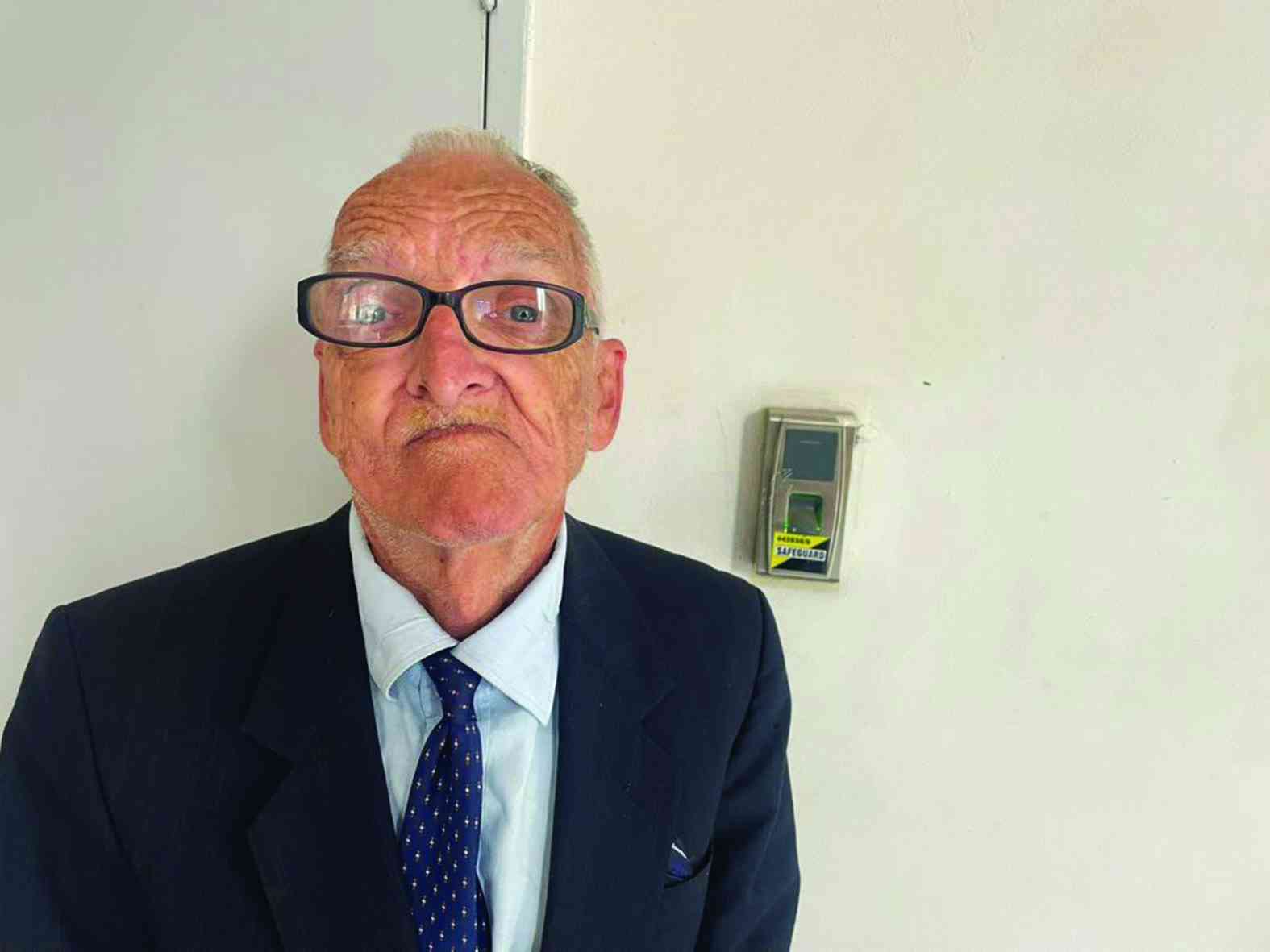

IN a modest room at the Salvation Army hostel along General Booth Road in Braeside, Harare, 74-year-old Graham Richard Bates holds the brittle pages of his past, a British passport that expired 12 years ago.

It is both his most cherished possession and a cruel symbol of his uncertainty.

Bates is one of a decreasing, often invisible generation of elderly British nationals who came to then-Rhodesia decades ago during the Ian Smith era, built lives, and now, in the twilight of their years, find themselves stranded.

They are pensioners without pensions, internationals without means, dreaming of a homeland many have not seen for half a century.

“I reside at the Salvation Army Baseline. I am a British citizen. I am 71 years old. Due to circumstances beyond my control, I am a non-salaried title holder and I just want to go home somewhere far from Africa to my relatives even though they are elderly themselves,” he said.

His story is a ledger of time and loss.

Born in Dewsbury on May 20, 1954, he arrived in Rhodesia in 1970 as a 15-year-old with his parents.

“I was a minor,” he recalls.

- Zim needs committed leaders to escape political, economic quicksands

- Chicken Inn knockout Harare City

- Ziyambi’s Gukurahundi remarks revealing

- Ngezi stunned by 10-man Herentals in Chibuku Cup

Keep Reading

“I was 15 years old when I came here.”

He later worked as an accounts clerk for six years at Seward’s, a clothing company

“I was very good with figures,” he said.

Now, his family is gone, parents deceased, a wife who has passed away, and his UK passport, issued in Harare in 2002, is an invalid booklet.

His monthly income is a survivalist’s arithmetic of US$64 from a local agency.

A passport renewal costs US$130.

An economy-class flight to the UK, a journey of hope, is a “prohibitive” US$500 to US$750.

“The numbers don’t add up. It is insufficient to live,” he said.

“I just want to get a sponsor. Someone that can help…

“If it is put in the (news)paper, then I might have a comeback.”

Bates’ predicament is not unique.

Aid workers and community advocates whisper dozens, perhaps more, in similar situations across Zimbabwe.

They are the remnants of a pre-1980 wave of immigration.

Some came as young adventurers or for work during the federation era, others were children of settlers.

They stayed through the transition to Zimbabwe, through its hopeful early years and its subsequent economic struggles.

Now, aged and often alone, they are caught in a web of confusion.

“The further north you go, the cheaper it is,” Bates muses about a potential UK home, ruling out expensive London for cities like Liverpool or Manchester.

It’s a pragmatic dream, shaded by the reality of a country he barely knows as an adult.

The barriers are a formidable trial of poverty, paperwork and proximity.

Many, like Bates, survive on minuscule or non-existent pensions.

Their British passports expired long ago, and renewing them requires fees, forms and biometric data, a daunting process from afar without support or funds.

Even with a valid passport, the cost of an air ticket is an impossible mountain.

They have no family in the UK to vouch for them or provide a destination.

“They cannot help me out. Even they themselves are elderly, above 90 years,” Bates said.

Charities like the Salvation Army provide crucial shelter, but repatriation requires specific intervention.

Organisations such as “Help Me Find a Sponsor”, to whom Bates has given his case, and others like the British Associations across Zimbabwe, work discreetly, trying to bridge the gap between desperation and bureaucracy.

The British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office states that it provides support to British nationals overseas in genuine distress, but repatriation is typically a loan of last resort, recoverable from the individual a prospect impossible for those with no assets.

For Bates, time is measured in football scores and quiet days at the hostel.

He waits, his cellphone number (+263 782 207 483) ready, hoping for an SMS that could change everything.

His story is a quiet postscript to a colonial chapter, a human footnote to history.

It is not about politics, but about basic human dignity, the wish of an old man, who gave his youth to a country now foreign to him in his old age, to simply go home.